BUSTING THE 20TH CENTURY

Students have little else with which to build the future but the lumber of the past. – Lewis Lapham

February 29, 2020

The great Lewis Lapham, former editor of HARPER’S magazine, said the above in response to the question, “How would you reinvent America?”. His words reference two undeniable truths: that students are the future, and that they would be well served to build it on a careful study of the past. As for reinventing America, it would need to learn from its mistakes by re-engaging with its own, and indeed, the world’s history.

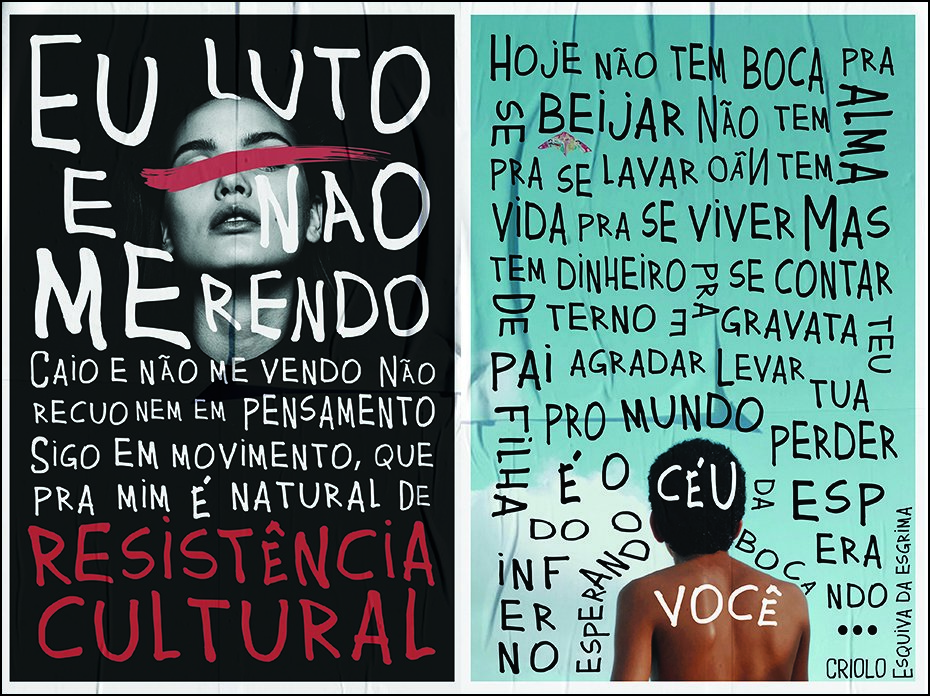

Wentz Greg, George Brown College / a project that tries to alter our misconceptions about Brazilian favelas

Anyone who has taught history to young designers and artists has likely struggled with the youthful impulse to discard the past and just get on with the future. And though that impulse is an essential part of anyone’s passage into adulthood, designers and artists educated in the 20th century are at least partly responsible for adding fuel to the fire. The entire edifice of 20th century art and design culture was built on an aggressive rejection of the past.

As discredited as 20th century modernism may now be for its heroic and monolithic stance, its dismissal of the past and obsession with the future continue to course through the veins and arteries of contemporary culture. Just listen to the language of ‘disruption’ coming out of Silicon Valley.

“It’s a time of opening and questioning the role of design in the world and the role of design education.”

Few would disagree with the notion that the purpose of education is to prepare students for the future. Typically that ‘future’ is the one imagined by a culture’s dominant ideology, whether religious, political, or commercial. The future that is currently being imagined for us in a culture dominated by commerce and celebrity seems to be one of unlimited growth, abundance and prosperity wrapped in a heroic sheen of technological innovation. But the realities on the ground are more like the opposite: increasing scarcity, inequality, conflict and environmental degradation.

What if that’s not the future we want? Is it the job of education to question the reigning ideology or to equip students for the workforce? Is it fair to view it in such a binary way? Can you do both? In design education in Canada, as elsewhere, there has been a spectrum of responses to this question. That is reflected in the conversations we had with the deans, professors and students at some of Canada’s leading post-secondary art and design schools. Here is what they had to say.

Space for the Speculative ~ Celeste Martin, Dean of Design at Emily Carr University believes this is a very exciting period of transformation for both design at Emily Carr and design itself. “It’s a time of opening and questioning the role of design in the world and the role of design education,” says Martin. She continues: “When we look back at what design and design education were in the 20th century, and where we have arrived, it’s made all of us deeply question our understanding of what we do. We’re no longer stuck in this terminal always vanishing present. We can look at the full implications of how our world is built by design, and how that affects us.”

This inquiry goes beyond questions about form and communications to ones about the kinds of behaviours that a design will encourage. “Design is intrinsically both destructive and creative. Making implies the unmaking of something else, whether that is resources or behavioural patterns. Here at Emily Carr we strive for being more fully aware of these impacts, and for a longer-term view of how to design rather than a presentist one.”

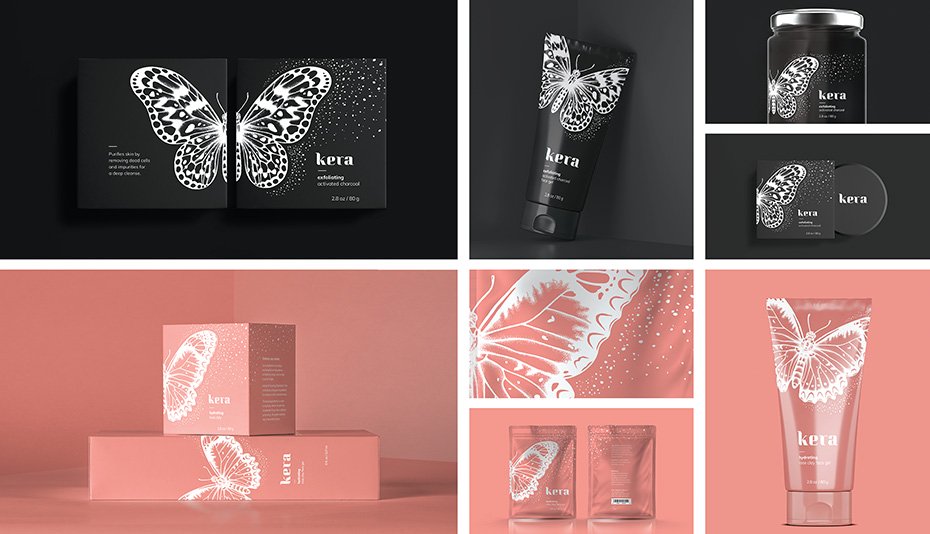

Aleksandra Isakov, Conestoga College / Identity and packaging for Kera Skincare

Don Norman, author of the iconic Design of Everyday Things and head of the Design Lab at UC San Diego, has said that with today’s large complex problems, design education needs to change to include multiple disciplines: technology, art, the social sciences, politics and business. We asked Celeste Martin what she thought of that. “I think to some degree it does. But in some ways, there’s a legacy of the 20th century heroic stance of design in that statement. I think design is starting to develop a certain humility of understanding that we do not solve these problems in the heroic stance but that we’re continually entangled, that we’re continually negotiating with partners outside the practice on an equal footing.”

This anti-heroic mindset is a significant departure from the modernist view of design as humanity’s chief problem solver and opens up the conversation for a more inclusive and respectful stance.

Celeste Martin and her colleagues at Emily Carr University are working to understand the creation of knowledge and to build relationships with industries or practices where “we can work together to allow for that space that is more speculative, that runs at a different pace. We are also working for people to be able to adapt to new jobs, to have a range of skills and a range of views that is not directed solely towards developing skills for the workplace.”

Surfing Silicon ~ Conestoga College in Kitchener-Waterloo takes a small step in the direction of Don Norman’s model of a design practice informed by multiple disciplines. Along with degree programs in architecture, interior design and graphic design, it offers a degree in engineering, which is a reflection of the fact that it is a polytechnic – neither a college nor a university. The focus is nominally on technical skills, but according to professor John Baljkas, a broad range of outcomes is expected of its graduates, including skills in problem solving, understanding of process and perhaps most importantly, critical thinking.

The fact that the college is located in the heart of the burgeoning tech cluster in Kitchener-Waterloo gives it immediate access to the software engineering and start-up community. “It’s not untypical for us to be approached by software engineers who readily admit that they can develop the apps but lack the skills for user interface design. We also encourage collaboration through events like our annual Creative Day for Social Good, in which students work with writers, creative directors and project managers from places like Manulife, Intertek Catalyst, HIM&HER and Google on developing communications solutions for non-profits.”

Through such partnerships, Conestoga appears to be heading down the road to more of a Don Norman model. Because of its proximity to the tech cluster it makes sense that the most likely early collaborators for Conestoga’s design students would be software engineers. But with two other universities in the immediate area, both with social science and business faculties, the potential for a more multidisciplinary model certainly exists.

Decolonizing Design ~ Dori Tunstall, Dean of Design at OCAD University, enjoys the distinction of being “the first black female dean of a faculty of design anywhere in the world”. Additionally she may be the first design anthropologist to hold that position.

One might wonder why an anthropologist would be chosen for this role. Tunstall explains: “In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations, OCADU was looking for ways to decolonize design education and introduce more indigenous representation on faculty and in the curriculum. I had done exactly that in my previous roles at Swinburne University in Melbourne, Australia, and University of Illinois, Chicago.”

Her experience with design outside of academia has been as an anthropologist with the mandate of codifying ethnographic processes so that any designers can use them to come up with the insights that would drive innovation. She did that at places like Sapient and Publicis.

Ethnography is powered by empathy, that rare ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, a quality at which good ethnographers excel but one that has been historically absent from much of design culture, save for the more human-centered approaches of the last 10-15 years. To introduce it into the design process represents a shift from what Celeste Martin called the ‘heroic stance’ to more of a humble stance vis-à-vis the world.

What does it mean to decolonize design? For a start, it means backing away from the narrative that design was something that began in Europe in the 19th century. With stone tools dating back 2.5 million years, we’ve been making design decisions a little longer than two centuries. Viewed through this longer lens, your perspective on design shifts from Eurocentric to humanity-centric.

“Our understanding is now based on indigenous principles about how you stand up as a person in the world.”

It also opens the door to other narratives, including those of indigenous peoples. How does that come to life within the walls of a design school with a Eurocentric legacy? The first sign of OCADU’s commitment was to hire a cluster of indigenous faculty who would be tasked with rewriting the curriculum. To illustrate with an example of how that might look, Tunstall tells the story of how a Metis industrial design instructor aligned the Seven Grandfather Teachings (humility, bravery, honesty, wisdom, truth, respect and love) with the steps in the design process. When considered through those seven lenses, design begins to take on a much deeper meaning and a much longer view.

Says Dean Tunstall: “That means that design is not just going from discovery to sensemaking to ideation to iteration to implementation.” Instead of just being a succession of functional phases the design process commits to deeper principles. “Our understanding is now based on indigenous principles about how you stand up as a person in the world,” continues Dean Tunstall. “That’s the kind of shift in thinking that we’re hoping to develop more and spread throughout this process of decolonization at OCAD University.”

Programming The Future ~ Like Emily Carr’s Celeste Martin, Ronni Rosenberg, Sheridan College’s Dean of Animation Arts and Design, believes we are in a period of great transformation and profound change in terms of how design is practiced, where it’s practiced, how it’s structured and what different opportunities there are. Given her multifaceted background as an architect, photographer, printmaker, graphic designer and teacher, if anyone is equipped to experience the transformation we’re going through, it’s someone with a multidisciplinary background as diverse and rich as Rosenberg’s.

Rosenberg’s resume brings to mind the kind of model they were trying to build at the Bauhaus a hundred years ago. Walter Gropius believed that the purpose of design was to combine the creative activity of the individual with the practical work of the world. We asked Rosenberg if that still resonated. “Oh, I think that’s truer than ever now,” she responded. The Bauhaus ambition was to build a multidisciplinary design practice with architecture in the lead and interior design, industrial design, furniture design and graphic design working with each other in support. Sheridan has a 21st century version of this in development.

Tanner Garniss Marsh, Conestoga College / Identity system for oko car sharing service

Rosenberg explains: “We are developing a reconceptualization of design for the 21st century. Design is all around us. It’s leapt off the page and has become a much more immersive, multi-dimensional experience. This new program is meant to give students a sense of how to talk to architects, urban planners, way finding designers, side event planners or community partners and really understand how you can transform spaces. The hope for this program is to really be the at the leading edge of redefining design education.” This ambitious and innovative program is currently waiting for approval by the Ontario Ministry of Education.

Program development is how Sheridan is responding to the profound changes we are all going through. Rosenberg continues: "The workplace in our industry is changing so radically. We’re working on a program focused on strategic communication that is meant to be the next iteration of journalism. We’re working on another program that’s about training producers to work with business so that they learn financial literacy, how to find funding, how to make a business plan, how to craft an HR plan. We’re creating a postgraduate certificate program that we’re calling digital product design. We see it as the next iteration of web design, focused far more on systems thinking so that students will understand how to design systems as much as the experience of systems, and are able to advise stakeholders from that perspective.”

In the midst of all this change there is one constant: the studio. Says Rosenberg: “Sheridan programs have dedicated studios loaded with all kinds of resources. Students know that these are the resources that they can count on, that they can call home. And then there’s a kind of stability to that environment and a richness to it. And the minute we give that up, then we lose what we are at Sheridan because for us, that’s what it’s all about”.

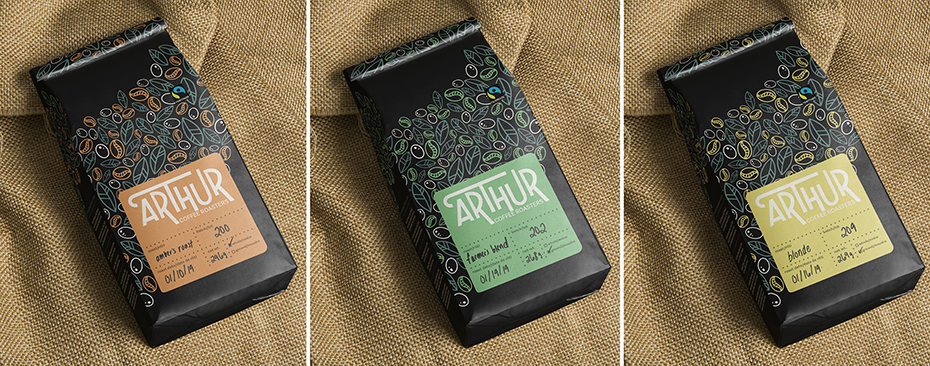

Katelyn Bradfield, Conestoga College / Arthur identity and coffee packaging

Solving Complex Problems ~ Over at George Brown College, Rosenberg’s counterpart has a similarly multidisciplinary pedigree. Dean Luigi Ferrara trained as an architect, worked for James Stirling and a number of Canadian firms before starting his own. He was also head of The Design Exchange for several years before joining George Brown. He has practiced architecture, urban design, industrial design, graphic design, branding and service design strategy. That’s more than a full kit for anyone looking to build a cutting edge 21st century design school.

We asked him what he thought the biggest challenges are for design today. “We have more complex problems to solve. When you’re trying to solve something like inequity or affordability or societal issues like inclusion, a single disciplinary approach is inadequate. You need an integrated design approach. And so we’re trying to train that way. We’ve had the opportunity to create a 21st century suite of programs. We introduced design management, digital design, game design, interaction design, digital experience design, and brand studies. This new type of curriculum is more reflective of the design challenges that employers, clients and designers themselves are facing in the 21st century.”

Some of this thinking began with the Institute Without Boundaries, co-founded with Bruce Mau back in 2003 as a special graduate program in interdisciplinary design. “What we’ve learned,” explains Ferrara, “is that the 20th century notion that form follows function doesn’t always apply. When function is continuously changing and problems are very complex, you actually need to create a new type of evolutionary design that permits the form and the matter and the scale of things to change over time. It needs an interaction between the community and the designer to maintain relevance over the long run. That’s a whole different way of designing, and a radically different approach when compared to the 20th Century paradigm.”

by Will Novosedlik

This story originally appeared in Applied Arts magazine. To subscribe, for just $29.99 a year, click here.

This by no means represents the breadth of offers, thinking and approaches in the many schools across Canada, but attempts to take the pulse of some of the more compelling streams of thought shaping today’s curricula. What we’ve seen and heard above are responses that range from humble to heroic and from technical to conceptual. There are some programs that reward deep, fundamental inquiry and others that embrace the speed of the age. But all seem focused on the future – even if looking back generations for guidance.