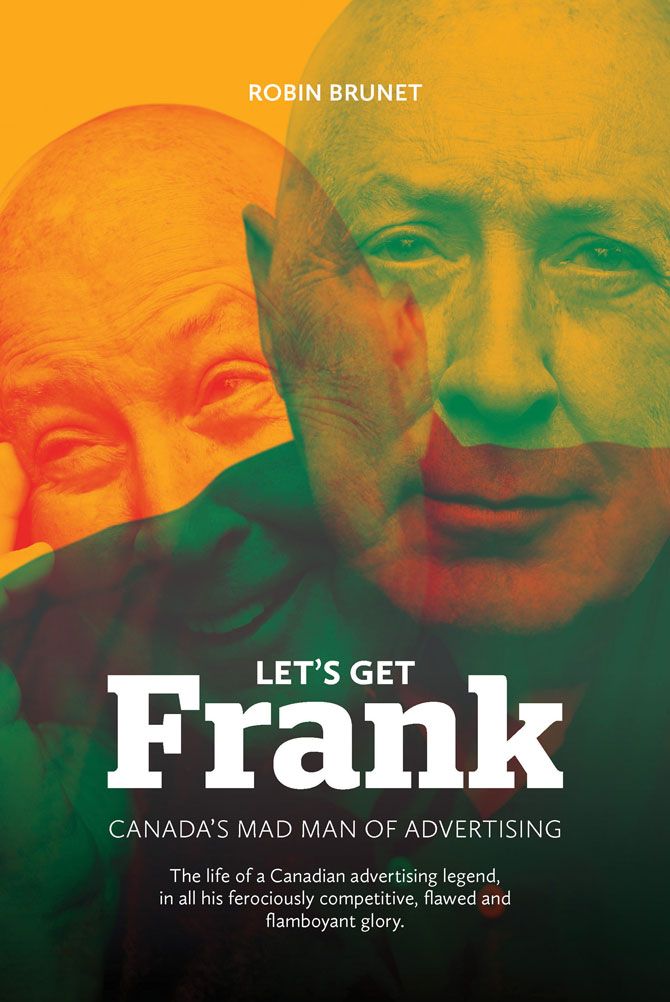

Getting Frank with a Canadian ad legend

May 2, 2018

He’s well into his 70s, but with a new biography and more business to be won, Frank Palmer shows no sign of slowing down

We’re already 55 minutes into a discussion about his new biography, Let’s Get Frank, a rambling conversation that has touched on everything from advertising’s declining fashion sensibility (“jeans and blazers and sneakers have taken over dress wear. I have to admit it’s more comfortable”), how procurement is killing advertising (“they do everything to persuade a client not to do good work”) and, yes, the famed hot dog story, but Canadian ad legend Frank Palmer still hasn’t had enough. “Ask me some more,” says the DDB Canada chairman and CEO. “I’ve got more time.”

First of all, how does it feel to have your whole life summarized in a book?

It was a labour-of-love project that we did over four years. I spent about two or three hours a week with the writer [Robin Brunet], talking about stories, about my life and what it was like to be in the ad business at just about the same period as Mad Men. I was living in the last era of the “Mad Men,” and they asked me if the show was close to that period. And I said “Yeah, it really was.”

In Let’s Get Frank, you say you’re probably the oldest guy in the business still operating at the same level. Most of your contemporaries have retired or left the business, so why continue to work this way?

I still love what I do. I was out with a client last night until 1 a.m. and in the office at 7 a.m. If I was out with one of my account directors until one o’clock in the morning and he was with me, I’d expect him to be in the office by 7 a.m. too. If you’re going to go with me, you’re going to have to roll with me.

I still enjoy the business, I still love the people I work with, and if I weren’t enjoying it, I would definitely leave the company immediately. I love seeing people create really interesting campaigns. This morning I interrupted two separate creative teams by asking them what they were working on.

You’ve enjoyed a long, varied career that includes an ACA Gold Medal and the Marketing Hall of Legends. What are you personally most proud of?

I started Palmer Jarvis in 1969, so next year will be 50 years. Of course, I was only five when I started it. There are a number of advertising agencies operating today [whose founders] came through DDB.

Most of the advertising agencies in Vancouver, their leadership has come from Palmer-Jarvis. I would say that 90 per cent of the agencies for sure—the people who run them all came through our agency. Their training was maybe too good, because they’ve all become very good competitors. We constantly have to learn new tricks.

Did you feel a twinge of regret when the Palmer Jarvis name came off the door [Palmer Jarvis DDB became DDB Canada in 2004]?

Yeah. It’s still in the floor though, when you get off the elevator. And if you talk to people in Vancouver, we’re still known as PJ.

Basically, at heart, we’re still PJ. If you asked me if I knew then what I knew 20 years later, would I still have sold to DDB? Yeah. We wouldn’t have grown to the same degree of success without being part of a multi-national. And as long as I’m still here there’s a certain vibe: I push people, hopefully in the best direction for our clients and services. There’s still a lot more to do, but it’s getting the clients to work with us.

Would you still recommend advertising as a career, and what advice would you give to young people entering the profession about how to succeed?

Even at the ripe old age that I am, I would have no problem starting another advertising company again today.

I still believe there’s a huge amount of opportunity, maybe more than ever before, to come up with creative concepts and ideas if you’re at least a little bit creative. There are opportunities to create a different model, maybe more like a film company where you’ve got a script, you’ve got a plot and you hire what you need to make that particular [piece of content].

You don’t necessarily have to have 50 or 100 or 200 people working in your agency—you can have a core of people that are experts in their area and hire freelancers for the need.

In the old days, you used to get pigeonholed in a certain area—you were a media person, or you were production person or a copywriter. Today, if anybody’s got any talent, they can be all of those things.

The industry has obviously changed since you started Palmer Jarvis. What has been the biggest change?

The business is almost on too much. You can’t go anywhere without seeing some form of advertising, which bothers the hell out of me. You go to the washroom and there are signs on the wall. Everybody’s trying to find a new way to get their ad in front of people.

As a veteran ad guy, why do you find that so distasteful?

Because when I want to turn it off, I don’t want to have to look at it.

I find that advertising has got to the point where it’s too much in our face. When you pay your $9 a month to watch Netflix, it’s not bothering you during your two-hour show. I don’t want to have commercials every 15 minutes.

That’s the business I’m in, and I understand it, but at the same time I want my own space without advertising. I don’t want to be on the beach in Hawaii and have somebody walking past me every five minutes trying to sell me something. Sometimes you just want to be left alone. Please.

When I’m spending time in California and watching the local TV, I’ll see a commercial come up for a Ford F-150. Within another minute or two, the commercial comes up again. When it comes up again in the next five minutes, I’ll say “I’m never going to buy that goddamn car. I’m so tired of seeing that commercial—you’re driving me nuts.”

I’m struck by the fact we’re talking with one of the giants of Canadian advertising, and he’s railing against the industry.

I still believe in the business of advertising. Great advertising works, but I still would like to go to certain advertisers and say, “I don’t want to be too rude, but your advertising is really bad. I’d like to help you do better advertising and I’m sure you’ll sell a lot more products or a lot more customers will look more favourably on you and your products.”

What is the single biggest problem with modern advertising?

The biggest problem is the fact that procurement is killing our business. Clients will say, “You can’t buy me a drink, because procurement says you can’t because you’re trying to persuade us into favouring you.” Of course I am. I’m trying to get to know you and understand what it is you love and your business and why you want to sell your product.

You don’t get that from procurement. They do everything to persuade a client not to do good work. They persuade a client to say, “Let’s buy this on an hourly basis.” If I go to the heart doctor and he says it’s going to cost $50,000 and take an hour, I’m going to be okay with that if that guy’s done some work before that has saved some lives.

Buying something on an hourly basis is the wrong way to think about it—you want an agency that’s going to get the best results. You don’t get everything for free—you don’t get the same car for $50,000 as the one you get for $10,000.

It seems like there’s a bit of a worry on your part that the relationship aspect of the business is being cast aside in favour of financial concerns.

My new agency model would be that unless the president of a company is willing to sit down with me and be my partner, I don’t want your business. [With DDB] I try to make sure that [staff] get as close to the client as they can.

When I had a relationship with a client, I would not only have the president’s ear, I would have the marketing director’s ear and the owner-operator’s ear, and they all knew I was working to do my best on their behalf.

If I was working with Nordstrom today, I would want to know the president, I would want to know the people in the marketing department and what the people on the sales floor are talking about. It’s just common sense.

Who are we trying to make happy here—the marketing director with a good campaign that’s going to win some awards, or a good campaign that’s going to sell more products or services? That’s the whole game. I don’t think we get that chance because when we win a piece of business, we know that three years from now we’re going to have to prove again that we’re worthy of keeping the business. It’s a no-win game.

Chris Powell is an award-winning writer whose work has appeared in Marketing, PROFIT and Reader's Digest.