Keeping Up with Moore’s Law

December 4, 2019

The digitization of illustration and photography has transformed these practices into a multichannel narrative that is as much about how the work gets done as it is about its final form and destination. by Will Novosedlik, Photo: Angela Gzowski

In 1965 Gordon Moore, co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and later CEO of Intel, wrote a paper that predicted the number of transistors on a typical integrated circuit would double every 2 years, until about 2020.

His prediction has long been proven true. In 1970 the transistor count of a typical integrated circuit was one thousand. Today it stands at a jaw-dropping twenty billion.

So how is this relevant? The doubling of transistors means a doubling of memory capacity and processing speed. It means more and more powerful sensors and bigger pixel sizes on digital cameras. It explains how we have been able to turn the mobile phone into a still and video camera and the once closed world of the professional studio into a do-it-yourself darkroom in a pocket. It partly explains how apps like YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram and Facebook have become so wildly popular as platforms for anyone with content to share. And it explains why every professional photographer and illustrator is into motion.

Then there are the exigencies of marketing. Ever obsessed with operational efficiency, corporations have seen Moore’s offer of twice the data at twice the speed as justification for demanding twice the output at half the cost from their creative partners. Traditionally obsessed with how to drive down media costs, now they are obsessed with analytics on how efficiently the money is being spent across the 40 or 50 potential channels at their disposal - and with whether or not the agency of record can deliver it all. Some are asking that if they need so much more visual content, maybe they should bring creative capacity in house or go direct to a photographer or illustrator, bypassing the agency altogether. Thus, in a world where speed equals profit, the creative ecosystem is being blown up by the corporate diktat of more and more for less and less.

Whether we are talking about the demise of print as a source of revenue or the rise of social as a distribution system, the last 5 to 10 years have demanded that a lot of practitioners re-examine their business models. They have demanded that educators change their mindsets and that students embrace the concept of entrepreneurship in addition to finding their artistic voices. And in a creative community built on building other people’s brands, they have forced individuals to build their own in the same crowded channels.

RYAN SZULC’s mastery of light and deep understanding of culinary has kept him head and shoulders above the DIY crowd while other food shooters watch their work dry up in the face of shrinking budgets and clients who expect more for less. Ryan’s solution? He raised his rates. Now he does less but gets paid more.

When the Story is the Story About the Story ~ If ‘digital’ is the most overused word in the post-modern marketing vocabulary, ‘storytelling’ is next in line. Despite the fact that humans have been telling each other stories for 150,000 years, it wasn’t until their marketing departments discovered the word in the 21st century that ‘storytelling’ became such a handy way of describing how we keep each other awake. Aided by the immediacy, interactivity and convenience of social platforms, along with their increasing capacity to deliver more and more kinds of content, stories have never had a bigger canvas.

But a bigger canvas needs planeloads of content. It follows that in this environment, a lot of the content – from fly fishing to fast frying – is about the making of the content. People love being brought ‘behind the scenes’ to see how stuff is put together. The internet is nothing if not the simultaneous opening of a billion kimonos.

One photographer who has perfected the art of social storytelling and digital brand building is Benjamin Von Wong. One of the most exciting image makers working today, Von Wong is famous for artworks of massively complex design which require days, weeks and a lot of collaborators to execute. He is also known for bringing voice to major environmental causes in very dramatic ways, and he does this in some of the world’s most physically challenging locales, from the lava fields of Hawaii to the shark-infested reefs off Bali to the sweatshops of Southeast Asia.

It’s a bit limiting to label BENJAMIN VON WONG as a photographer. His final images are only one component of his multifaceted output, for not only does he create amazing stills, but shoots them in impossibly challenging locations, documents the process, often repurposing sets and props as art installations and sharing the story of each creative endeavor through videos that are seen around the world.

“Each one of these shoots is photographically documented and spread around the world, sometimes in the form of a behind-the-scenes video”, explains his rep Suzy Johnston. The impossibly challenging circumstances are never a match for him and his team’s unbridled passion, humility and determination, which is what makes these behind the scenes stories so irresistible. The finished product –- as spectacular as it is – is only one part of a much bigger story about the location, the objective, the obstacles, the people, the ingeniously engineered solutions (Von Wong was a mining engineer before becoming a photographer) and ultimately Von Wong himself and his very authentically crafted brand.

Instagram, the Great Disruptor ~ Other photographers have succeeded with less intense engagement of the social channels. Angela Gzowski has been shooting for 6 years. She operates in a secondary market – Yellowknife, NWT. She lives there because it’s where she grew up and she loves it. After a few years at school and work in Halifax, a job offer at a regional magazine brought her back home. Now she works for a variety of clients from Canadian Geographic to Netflix. I asked how they found her.

“Well I am not 100% certain where all the referrals come from, but I do know that Netflix found me on Instagram”, she says. Which naturally leads us into a conversation about how social has either helped or hindered her business. Gzowski’s digital footprint is pretty small. She posts on Instagram. She used to post on facebook but not anymore. “There’s too much crap on there”, she complains. “And it’s time consuming. There aren’t enough hours in the day to keep up.”

“If you are trying to get established as a photographer you need to be on Instagram. At the same time, clients who reach out to you on Instagram are the ones who are not willing to pay because they have a perception that if it’s on Instagram it’s going to be cheap.”

Toronto-based photographer Wade Hudson has mixed feelings. “If you are trying to get established as a photographer you need to be on Instagram. At the same time, clients who reach out to you on Instagram are the ones who are not willing to pay because they have a perception that if it’s on Instagram it’s going to be cheap.” That’s because so many wannabe shooters are far more interested in getting likes than in getting paid. This is training clients to expect everything for ‘free’.

The other problem is that most clients can’t really tell the difference in quality. “So you’re getting situations where quantity is now the driver. If a client can’t see the difference in quality, they are not going to pay your professional day rate for 6 or 7 shots when they can get 120 frames from an Instagram influencer who is happy to be paid with merchandise”.

So why be on Instagram at all if you are a pro? Hudson says it’s not so much for getting clients, but for meeting collaborators, people who can help you with your work or with whom you can work on their stuff.

Matt Barnes, who works out of West Side Studio in Toronto, says it’s a great way to find unusual props like 1959 Cadillacs. Looks like everyone’s getting something out of it. Just not always the same something.

The authenticity of these portraits by ANGELA GZOWSKI betrays the photographer’s love of the north and its people. Having grown up in Yellowknife, Gzowski returned after several years of school and work in Halifax and has prospered there, taking plum assignments from the likes of Netflix and Canadian Geographic magazine.

Death by DIY ~ Veteran food shooter Ryan Szulc notes that the advancements in mirrorless cameras have enabled anyone with a smartphone to call themselves photographers because “the honest truth is, it’s not all that hard to make a pretty picture.” Nowhere is that more obvious than in the world of food. “The whole DIY thing has alerted cost-conscious clients to the fact that they are now in a position to put greater pressure on professionals when negotiating fees.”

For Szulc, cookbooks were always a big source of revenue. Used to be that a photographer would be hired directly, but now publishers will offload that responsibility to their authors. “The author will receive an advance which has to include the cost of photography. Let’s say it’s an advance of $60K. The client wants between 80-100 photos. The photographer comes back with an estimate of $40K. Well their eyes just bug out and before you know it they are talking about getting one of their nephews to shoot it instead. When you have a studio and staff and rent to pay, you just can’t compete with that.”

Not wishing to get trapped in a race to the bottom, Szulc’s response to these conditions has been to raise his rates. It was the right thing to do. It separated him from the DIY pack and signalled to clients that he was at a higher level of experience and expertise. “I don’t have as many projects on the go as I used to, but the budgets are much higher.” There’s something to be said for placing the right value on your work.

There is a significant cost to these changes in the perceived value of photography. Sports and entertainment photographer KC Armstrong talks about how along with a decreasing appreciation for quality comes a decline in the perception of the overall value of photography. If anybody can make a ‘pretty picture’, why pay a pro to do it?

The Notion of Motion ~ The world of print is a world without movement. Once the ink hits the page, the impression it makes is frozen in time. All of the workflow, all of the thinking and all of the creativity that goes into print is defined by this fact.

A page on the internet, powered by Moore’s Law, can support a billion times more data than a page in a book or a magazine. So why settle for still imagery when you have the memory capacity to stream a film?

The volume and speed of digital delivery demands the same of its content: it wants lots of it, delivered at speed and refreshed with regularity. So the practitioners of an industry built on stills have moved into ‘motion’. Every photographer we spoke with for this article is becoming a director. Some are further down the path than others, but everyone is on that path.

“I know a picture is worth a thousand words, but you know with video you can also say the thousand words.”

For West Side Studio’s Nikki Ormerud, the opportunity came from a production company. They bet that she could do motion as well as she did stills – and they won. We already mentioned Benjamin Von Wong, for whom the line between ‘still’ and ‘motion’ is crossed so often that it has all but disappeared. Wade Hudson, whose work is split between stills and motion, has recently produced a documentary for BMO. As Hudson points out, “I know a picture is worth a thousand words, but you know with video you can also say the thousand words.”

Illustration Rides the Wave ~ So how has Moore’s Law affected illustration? I asked Steve Mykolyn, former Chief Creative Officer of TAXI Advertising and Design. “It has truly made photography more of a commodity, but not illustration. Remember: you hire an illustrator when your idea can’t be photographed. So illustration will never be a DIY thing. There are no tools, devices or apps that will create an original illustration on demand.”

The other important point Mykolyn makes is that with photography, “you pretty much know what you are going to get. Hire a Ryan Szulc to shoot some garlic for you and you know you will be getting a beautifully lit, sensitively styled photo of garlic. Give the same assignment to an illustrator, and she might come back with a picture of a vampire with a garland of garlic around his neck. In both cases you get what you want, but with photography you know what to expect; with illustration it’s always a surprise.”

Moore’s Law will never change that. But it has changed the practice. Having pushed print to the wayside, the forward march of digital has seen one of the illustrator’s traditional sources of exposure and income evaporate. There was never much money in it, but editorial has always been a premiere platform for the display of conceptually brilliant illustration.

Bob Hambly, designer/illustrator and co-founder of the longstanding firm of Hambly & Woolley, talks about what that has meant to his career. For 12 years he did a weekly illustration for the New York Times Sunday Magazine. For 5 years he was commissioned to produce 3 illustrations a week for TIME magazine. Graham Roumieu has a similar standing gig for the back page of Atlantic Magazine. And then there’s Barry Blitt, who has delivered more than 100 covers for the New Yorker. These are not only steady gigs. They are the most prestigious gigs you can get. But for every one of these, there’s a graveyard full of decommissioned newspapers and magazines, burying what used to be one of illustration’s most important platforms of expression and exposure.

The Many-tentacled Practiioner ~ Gary Taxali is a creative octopus. The celebrated Toronto-based illustrator, professor and fine artist has built a growing repertoire of what might be called ‘brand extensions’ of his signature imagery. It can be found on skateboard decks, Harry Rosen pocket squares, coins by the Royal Canadian Mint, Hobbs & Kent cufflinks and a line of toy Taxali characters for Chapters Indigo. And as if that isn’t enough, his fine art paintings have been exhibited in New York, Montreal, London, Sydney, Milan and Amsterdam.

“I take bigger risks in my fine art, which gives me the confidence to expand the vocabulary of ideas in my more commercial work.”

He talks about how one practice area informs the other. “I take bigger risks in my fine art, which gives me the confidence to expand the vocabulary of ideas in my more commercial work.” He reminds us of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami, whose cute little mouse figurines are designed to delight little children while the same figures are rendered as giant flesh-eating monsters in his fine art.

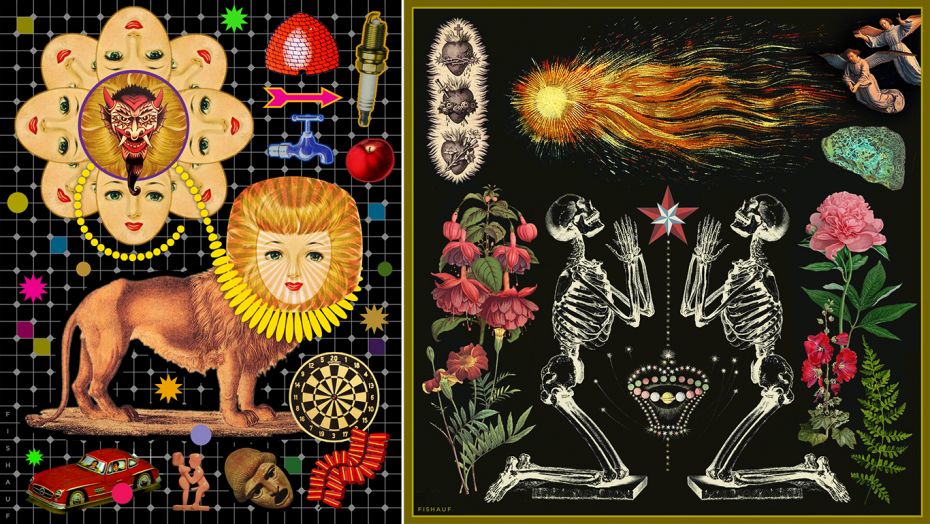

Editorial design master LOUIS FISHAUF has long delighted us with his illustrations as well as his covers and spreads. These images are part of a series of personal works, in which the artist displays not only his encyclopedic ability for finding intriguing archival imagery, but also his mastery of montage.

Taxali and a growing number of other practitioners are showing us what it takes these days to survive as a professional illustrator. Gary Clement, who has done an editorial cartoon for the National Post every day for 21 years, has also appeared in Mother Jones, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, TIME and The Guardian, has published award-winning children’s books and has a thriving fine art practice. Graham Roumieu has supplemented his editorial work for The Atlantic, the New York Times, Harper’s and The Wall Street Journal with his now famous Bigfoot-themed series of books In Me Own Words: The Autobiography of Bigfoot, Me Write Book: It Bigfoot Memoir and Bigfoot: I Not Dead. With such a variety of art forms in his portfolio, Roumieu has a bigger footprint than Bigfoot himself.

The writing on the wall is that, increasingly, you can’t just be an illustrator. You need to be as much an entrepreneur as an artist. And you have to be fiercely original. Chrystal Falcioni, founder of LA-based Magnet Reps, counts Graham Roumieu as one of her artists. “I am seeing two things these days. One, the number of illustrators in the market is enormous, making it tougher to compete. And two, social media’s exponential growth has created what we might call stylistic filter bubbles. People tend to mimic the trends they see in their social and professional circles and the result is a lot of work that looks the same. To me, that’s becoming a very risky choice.”

Gaming: the New Editorial? ~ Joe Morse is coordinator of the Honours Bachelor of Illustration Program at Sheridan College outside of Toronto. He is himself a very successful illustrator, enjoying relationships with clients such as Universal Pictures, Nike, Coca Cola, and several major league sports teams. He agrees with Falcioni that the number of illustration graduates is a challenge. “Illustration programs remain a popular choice for many students who see it as a viable creative career. We had 200 international students lining up for 7 spots this year. We graduate between 80 and 90 students a year. OCAD University has the largest program in terms of student numbers, with over 600 students.” Morse says he has always fought for smaller numbers in the classroom but it’s an uphill battle as universities here struggle to meet funding requirements by putting more and more ‘bums in seats’.

So where do they end up? Long-time designer and illustrator Louis Fishauf, who teaches in the OCAD program, confirms that many of them hope to work in the gaming industry, which has exploded in cities like Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. “Every year I ask students what practice areas they are interested in. Character design and gaming are at the top of the list”. Gaming may be the new editorial for illustrators, but as with editorial, it isn’t for everyone. Says Fishauf, “This semester I had almost 90 second-year illustration students. I don’t know how many of these students will actually find work as illustrators when they graduate and enter the market in two years”.

The Way from Here ~ Increased competition, digital transformation, the exponential growth of social media – these are some of the key forces shaping both illustration and photography today. As tough as they have been on professional photography, they have opened up some new opportunities for illustration.

At the end of the day, there will always be room at the top for the very best photographers and illustrators. But the top is a small place. It’s the massive middle where it will be tougher and tougher to make a living. That massive middle, populated by DIYs and clients who can’t tell the difference, and powered by an Internet with a rapacious appetite for content, is not likely to stop expanding. Moore’s Law may be approaching its expiration date, but it has made its mark. And the creative industry will never be the same. by Will Novosedlik.

This story originally appeared in Applied Arts magazine. To subscribe, for just $29.99 a year, click here.