On Advertising's Self Esteem Issues

If we don’t attach real value to our ideas, why should our clients?

July 21, 2014

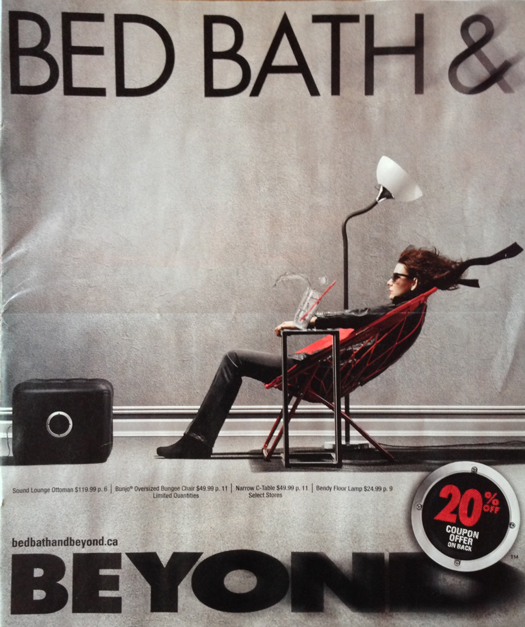

Last week, I got an interesting flyer from Bed Bath & Beyond.

The flyer is devoted to helping university students outfit their dorm rooms for the coming school year. As such, most of its audience is too young to recognize the source for the idea behind the cover image.

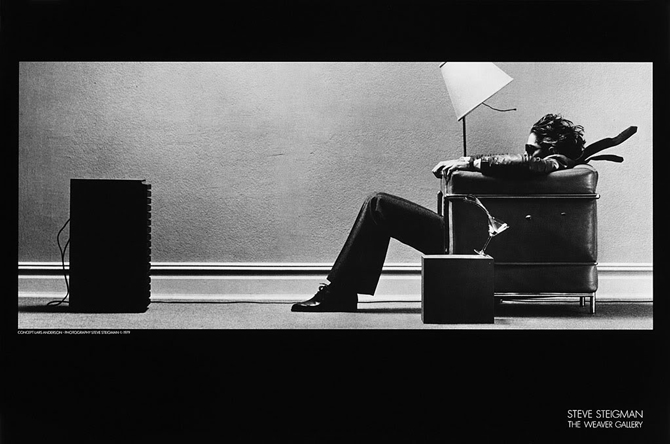

This photo, shot for Maxell cassette tapes in 1979, became an instant meme of the pre-digital age. It appeared on T-shirts, posters and Maxell packaging, as well as in TV advertising and countless parodies. Maxell resurrected the original image in 2005, and it even appears in the current Maxell logo.

The photographer, Steve Steigman, was a pioneer in establishing today’s limited-rights compensation model for photography. Thus, the Maxell image — the most famous of Steigman’s career — made him a wealthy man. But that photographic cash cow would not have existed without its concept, and that came from the art director, Lars Anderson of Scali McCabe Sloves. You can find Lars credited on the poster image above. Just look for the teeny tiny pixellated mice type parked under the left side of the photo. Yeah, it’s really small, but trust me — it’s there. So, for the idea that enriched a photographer and established Maxell as the premium brand in audio media, Lars won a bunch of awards and probably a decent raise and…um…not much else. As for the agency, Scali disappeared in 1993 in an acquisition by Lowe Worldwide.

Typically, an agency that authors a groundbreaking idea gets extra compensation only through awards and, perhaps, the opportunity to extend the campaign. Consider the recent licensing of the “Dumb Ways To Die” characters by Canada’s Empire Life. The characters were originally used in a campaign for Australia’s Metro Trains.

The press coverage around the matter has been all about Metro Trains’ success in capitalizing on the idea through, among other things, plush toys.

McCann, the agency responsible for this viral smash, barely has been mentioned at all. However, the client did hint that the licensing deal would be good for the agency: “We now have some funds to reinvest into more creative content,” says Leah Waymark, Metro’s general manager-corporate relations.

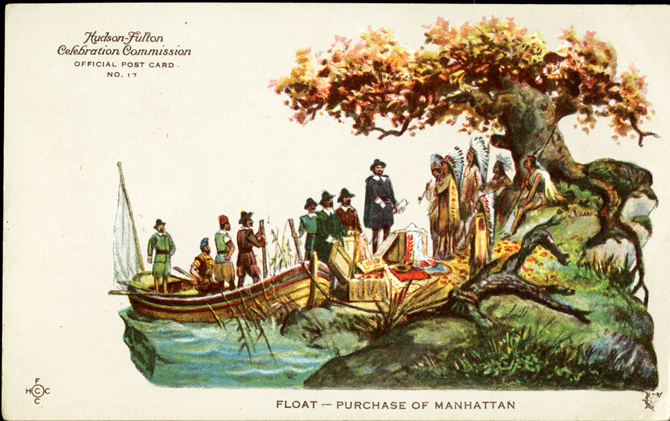

Should a client own an idea this powerful and lucrative when all it paid for was the agency’s time? It is true that McCann was rewarded with an unprecedented five Grand Prix wins at Cannes. But given our industry’s absence of long-term memory, any agency’s contentment with awards alone could be likened to another famous exchange involving shiny trinkets.

Certainly, ad people are smart enough to know that the business model is broken. We’ve all been through uncompensated pitches that have us offering up spec creative against a suspiciously long shortlist of competing agencies. We’ve all talked about refusing to work that way. But we know most agencies can’t afford to be proud, and so almost everyone continues to play along.

Ad agencies have spent decades discounting the value of their thinking. Yet, far from winning the gratitude and support of clients, this passivity has only invited more intrusion. We are now seeing the growing popularity of 120-day payment terms, a practice that has even small agencies and their smaller suppliers effectively making interest-free loans to the likes of Mars, Mondelez and Anheuser-Busch InBev.

Today, agencies are stretching themselves thin to offer and bill for services that didn’t exist twenty years ago. But the business still isn’t charging what’s fair for the thing advertising does best — nailing the moneymaking idea.

It took just one respected shooter to change photography’s compensation model forever. Could one respected agency achieve the same goal for all of advertising?

Toronto freelance copywriter Suzanne Pope is the founder of Ad Teachings.