The New Heretics

November 3, 2014

Apathetic. Self-indulgent. Insubordinate. Pick your stereotype — millennials have been called them all. Some young creative entrepreneurs are silencing naysayers with successful shops and a heady approach to business that may be different, but not wrong

It’s Friday, 2:00 p.m., and the offices at Playground Inc. are completely empty, save for a bearded fellow resting his feet on a couch in what can only be called “the video game room.” I check my phone to make sure this is the place and time. And it is. I gently knock on the glass wall of the room — where, next to a plush couch and boardroom table, sits a giant flat-screen TV plugged in to every gaming console imaginable. The fellow looks up from his Macbook.

“Umm, you seen Ryan?” I say. “I’m here from Applied Arts.”

He looks unfazed, so I continue. “You know, the magazine. I’m here to interview him.”

“Hmm, okay,” he says flatly. “One sec.” He makes a phone call, repeats my name and the name of the magazine, and after hanging up tells me to wait. “He’ll be a few minutes.”

I spend the next 15 minutes marveling at the circus-like cornucopia of graffiti, antique arcade machines, giant Domos and tiny trinkets that fill up this so-called place of business. If I didn’t know better, this could easily pass for the bedroom of some megalomaniac’s spoiled middle-schooler, who for some unknown reason has a collection of twenty iMac workstations in the middle of his hedonistic fun-time lair.

Finally, he shows. Ryan Bannon, the 28-year-old co-founder of Playground digital creative studio in Toronto, is a tall bearded man, built like a lumberjack, wearing a knit short-sleeved button-down. Just as I get ready to set up for the interview, he tells me not to get too comfortable.

“Sorry man — we’re all eating sushi up the street,” he tells me. “The cab is waiting outside, let’s go.” On the ride over, I meet Dave Senior, the 30-year-old chief growth officer, who apologizes profusely for the mix-up. Bannon tells me things have been crazy recently. Curiosity gets me, so I ask him why.

“Well,” he says. “I just became CEO.” Sounds like big news on paper, but he tells it to me as if we were discussing foods we used to think were gross. Slightly irritating, nothing huge.

________

And thus began my third interview while researching the berated generation we call the “millennials” (also known as Gen Y). What a perfect example, too, for it is this generation’s slack conventionalism and wild way of doing business that are hallmarks of the breed. Playground and company represent the quintessential millennial office culture, complete with unlimited vacation days, video games galore and a photo booth that Bannon tells me sometimes doubles as a “Phish concert–streaming room.”

But this cohort of people, born anytime after 1982 until around 2000, are defined most by what they inherited from their parents. And it’s not all that pretty: a gruesome economic meltdown, unprecedented levels of debt and unemployment, and a penchant for feeling special — part and parcel of growing up as “trophy kids,” or those lazy, entitled brats who got ribbons just for participating.

What I would discover while meeting up with a few cutting-edge, millennially helmed design agencies in Toronto and Montreal is that these stereotypes are, for the most part, rubbish, and at the very least misleading. We millennials are hard-working dreamers who are changing the world and the ways things get done. But we’re not doing it with a hell of a lot of job security, neckties or willingness to be bored.

RECESSION SUCCESSION

Ask Bannon, and he’ll tell you there’s no real difference between Gen X and Y. We just happened to get screwed with the whole timing thing.

“There are shitty people in every generation, and great people in every generation,” he says. “It’s easy to point the finger at millennials because they are inheriting the world. But you have to remember, we also inherited a really fucked-up world that has suffered from really horrible policy decisions and corporations running rampant on governments.”

In 2008, as the recession hit, the oldest millennials born in 1982 were just turning 26. In September 2009, Bannon had been out of school a few months and the job prospects were next to nothing — so he and a few of his fellow Seneca College advertising students did the only thing they could to stay in the business. They started their own company and took every measly gig they could snag, including radio spots for dentists. Impressively, though, five years later they’ve parlayed that early labour into exquisite success, gaining acclaim from the developer community and design experts alike.

Illustrations for Muse InteraXon by Playground

Illustrations for Muse InteraXon by Playground

On the other side of the fence, the namesake co-founders of another Toronto design firm, Whitman Emorson — Whitney Geller, 31, and Yasemin Emory, 32 — were lucky enough to have plum jobs in Chicago and New York City, respectively, as they watched the world’s financial structures crumble from their cubicles. But they didn’t want to stay put. They had to get out.

Emory was working at a major publishing house when she witnessed half of the company get laid off — and it was then she started to realize her plans for working in print might not have been so airtight. So when Geller, a friend from McGill University, came to her with a pro bono project, she jumped at the opportunity. In no time, the pair established an identity and reputation. They would keep moonlighting until they could pay the rent, at which time they promptly said goodbye to their respective cushy jobs and went off on their own. Eventually, they moved back to their hometown of Toronto, and in spring of 2012 opened their own office space, with their names on the door.

It’s a similar story in Montreal with Julien Vallée, 31, and Eve Duhamel, 32, who run an avant-garde studio called Vallée Duhamel, which specializes in high-quality, low-fi videos and installations for a luxurious and jaw-dropping list of clients including Hermès, Google and AOL. To them, the recession actually burst open the doors to competing with the big guys. Their target clients had shrinking budgets, which was not a problem for the upstart Quebecers.

“It was the best thing to ever happen to us — these big companies came to us, apologizing about their budgets, but we were like, ‘it’s cool!’” says Duhamel.

The team at Whitman Emorson

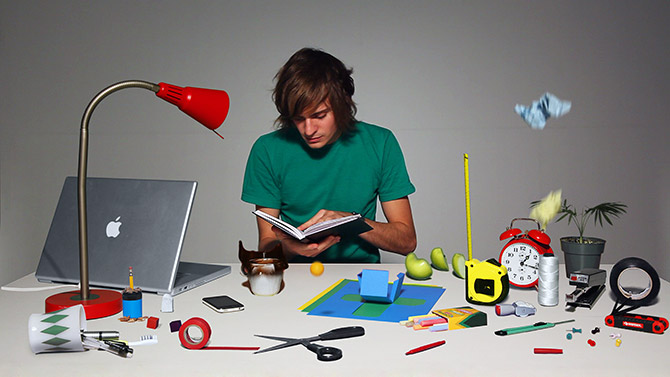

Julien Vallée of Vallée Duhamel

THE TRUTH ABOUT STEREOTYPES

I’m sitting in a café-slash-brewery on College Street in Toronto, staring at a magnificent and irresponsibly large selection of micro-brew beers. There are at least 20 polished silver taps, behind, a gorgeous hipster barista waiting to serve me. The perfect metaphor, I thought, for a generation known as lazy, entitled hedonists. I mean, how many fruity, chocolate-hinted beers do you really need on a menu?

Moments later, Emily Tu and Edmond Ng, 30-year-old co-founders of the symbiotically named Tung graphic design firm, meet me at the bar. As we sit outside to sip on our apricot lagers, I notice they are also handsomely dressed hipster nerds. Our discussion quickly moves to the origin story of their own studio, which, at less than a year old, is only just beginning to make a name for itself. (Tung’s website, I have to say, already possesses a mesmerizing little animation. You should check it out, right now.)

Their story takes on a familiar curve: they worked their asses off as interns. Then they worked up the ranks at some agencies in the city, including Underline Studio and Concrete Design. But they simply weren’t happy staying put. They wanted more. Specifically, they wanted to be the boss.

“I just wanted to be able to do my own thing, to have a sense of autonomy. It’s not that it was bad where I worked,” says Ng. “But I wanted to be able to make the decisions.”

It’s this line of thinking that leads people to see the millennials as entitled. We want to be the boss, to be treated as gold, without logging the hours or the sweat and blood. But the Tung founders don’t at all seem to be “entitled.” They just wanted to skip the bureaucratic malaise they knew from working at larger firms — places without much upward opportunity and millions of cc’s on the email chains. And, as Ng puts it, they simply wanted “to be able to shape the culture.” It doesn’t hurt they simultaneously were able to learn the ropes on all sides of running a business, which they otherwise wouldn’t have seen as simple cogs.

Ben Weeks identity by Tung

Back over with Geller, the co-founder of Whitman Emorson, she points out it’s this entitled spirit that pushes her generation to do great things, because we go after what we feel we deserve. But this has its downside.

“We are entitled, we were spoiled,” she says. “This works out in a good way for some if you’re lucky…and a crushing defeat, staying at home with parents, if you’re not.”

It’s this hunger to do new, great things that pushed Whitman Emorson to launch, of all things, a side project start-up selling custom wallpapers, called Thoreaux. With it, they repurpose lush and ornamental old prints — culled from 19th-century British illustrations and ancient Egyptian patterns, to designs from 1850s Paris and 12th-century Turkey — giving them new life on the walls of Gen Y’ers everywhere. It’s a venture in its early days, and who knows how it will fare. But the uncertainty seems less important than doing something they all feel is beautiful.

Dave Senior, the Playground chief growth officer, agrees in spirit. Millennials were set up to expect great things — but maybe not prepared for the hard work it entailed.

“Parents, all they told us was to go out and be happy — they forgot to tell us they worked their asses off to get where they are, so now we have to walk a fine line of being stable and happy,” Senior says.

But whatever the root cause, no one can argue that this feeling of entitlement equals laziness. In fact, Duhamel argues that it’s the opposite.

“It’s not lazy to not be satisfied with a steady job, with never settling down. It’s tough, a curse even. But it’s not lazy.”

Thoreaux wallpapers by Whitman Emorson

THE FRUITS

Back at the sushi restaurant, most of the Playground team is busy munching on expensive-looking sushi rolls and downing fancy pudding shots. It’s the weekend, after all.

“What we’re doing here is all about people and culture, making lives better,” says Bannon, whose digital company takes after the start-up culture of Silicon Valley —— i.e., putting people before (or as an avenue to) profits.

Millennials are often loathed for being self-obsessed, narcissistic and, although somewhat idealistic, more concerned with themselves than the world. In short, it’s the generation of the selfie. But it’s people like Bannon who reveal the leaders of this generation are not in it for the vanity, but are cursed with a lofty desire to change big things. Senior, Bannon’s partner, tells me about how the “web is this place where we all live now.” And, he continues, his team is bent on making the web, and hence the world, a better place.

In the same vein, Whitman Emorson people often take on pro-bono or lower-paying gigs that align with their sense of social purpose. And we spent more than a few minutes talking about a famous TED video, where the CEO quits his job every seven years to take a sabbatical. That’s something they want to do, too.

“We don’t think we’re better than anyone. We just know we can show the world in a different way,” says Geller.

Still, whatever your lofty dreams are, Ng at Tung says you might still want to consider doing the intern track on your way up. There was enormous value in learning from the bottom, he says. But eventually, you’ve got to cut the cord and go it on your own.

WORLD WAR Z

It was interesting to note how the next generation, that one called “Z” — the kids of millennials — was nudging its way into this story from the start. After a few emails trying to set up an interview with Duhamel and Vallée, we had to postpone a month because they each had kids to watch over the summer months. As Whitney left the table for the first time after our interview, I noticed she had a baby bump (she’s expecting this November).

And just yesterday, I picked up a Maclean’s article all about this next generation, and how they will be so much better than the Y’s that came before. These guys, it argued, won’t be so narcissistic. Won’t be so self-obsessed. Won’t be so slack. It led with the example of a little girl who invented a flashlight that is powered by the warmth of your hand. And it said: this generation will save us.

Funny, though. Maybe it’s true. But the millennials, the ones who bore the scars of the economic disaster, the ones who suffered the rude awakening that “in the real world” we don’t get ribbons for our good behaviour — these ones will pass on to the next the lessons of the past and the aspirations for what they didn’t quite get right. Just like any generation before them.

Now if you’ll excuse me, my Tinder is blowing up.

_____

Tobin Dalrymple is a writer — and millennial — living in Montreal. Find his fiction and journalism work at tobintobin.tumblr.com.

We're making most of our print content available online, free of charge, for your enjoyment through the end of the year. Content from our current issue will be viewable for two weeks, and reposted after the issue is off newsstands. In 2015, this content will be available to subscribers only.

Look for more content by these millennial-owned studios in the top slider.