The Public Studio: Design as Activism

March 31, 2022

Design is a practical art, and as most of us embark on our careers we don’t give a second thought to the fact that we are on a path to commercial servitude. That may seem cynical, but most of us spend our working lives toiling in the vineyards of capitalism, which, like colonialism, is an exploitative, extractive enterprise.

So when a designer or design firm comes along that sits entirely outside the pre-determined narratives that capitalism and colonialism have imposed on us, I sit up and take notice. The Public is just such a firm, and its co-founder Sheila Sampath is just such a designer.

In method, intent and product, The Public sits well outside the conventional paradigms of design practice. Part community hub, part creative collective, part radical incubator, it is a practice not based on making objects but on building social relations. In Sampath’s words, “What it's become is an all-encompassing practice in radical reimagination through a political lens. That means design is everywhere. It means design is practiced when we think about how to run a meeting accessibly. It means that design is practiced when we talk about a diversity of tactics for organizing an action. It means that design is practiced in collective living. All of those things require us to imagine new possibilities.”

Send the Right Message is a campaign that encourages straight and cisgender high school youth to challenge everyday instances of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia. Client: Planned Parenthood Toronto.

Just as her practice is unconventional, Sampath came to design in an unconventional way. She did not know she wanted to become a designer. Coming from a family of mathematicians and scientists, she originally went to school for engineering, but quickly discovered it was not for her. She then switched her focus to artificial intelligence and cognitive science. “I found the AI program at U of T very interesting because it holds space for psychology, sociology and philosophy. I slowly dropped everything that wasn’t sociology and psychology and still got a degree in honors science.”

While pursuing her studies she got involved in the Toronto rape crisis centre, a feminist antiviolence organization. “That was where I my interest in activism began. You come there in times of trauma. You come there from places of anger, and it has the capacity to transform oppression into hope and radical imagination. It's fueled by hope and possibility for another kind of world.”

Visual Identity for Women’s Shelters Canada

And it was there that she was informally introduced to graphic design. While helping to organize Take Back the Night, an annual rally for and by trans people, she was asked to make a poster. She enjoyed it, and received many compliments for it. Even so, she still saw design as a very superficial activity. She decided to explore it further and enrolled at George Brown in the hope that she could use design to bring more people into social justice movements. But she did not find that the curriculum operated with a sufficiently critical social lens.

She has done a lot of student mentorship, and in that work she’ll often find herself at odds with the frameworks of conventional design practice. “A student might come to me and say, ‘I want to do something for planned parenthood’. And then there are teachers who will look at that through a highly corporate lens and ask, ok who’s the competition? That thinking does not come from a community-based mindset.”

Capitalism has a way of appropriating every narrative, even when an organization ostensibly declares an interest in decolonizing itself. For instance, Sampath refuses to join the RGD. She has been invited to do so. “They told me that if I joined they would put me on this panel and that, and I’m like, no, you don’t get to take our community skills, our knowledge, and sell it back to us.” Sampath has no interest in being the poster girl for decolonization.

Sampath has taken on various teaching contracts. She taught a class at OCAD on research methodologies and the ways in which designers and researchers could start to imagine methods that are more community-centered and not so focused on consumption. She taught a class called open studio, which was about critical and speculative design. Says Sampath, “We developed curriculum that looked at indigenous futures and designing for the world that we want to live in, and creating critical objects for us to better understand and interrogate the world we are living in now. I teach everything through an activist lens, because I really can’t leave that part of me aside.”

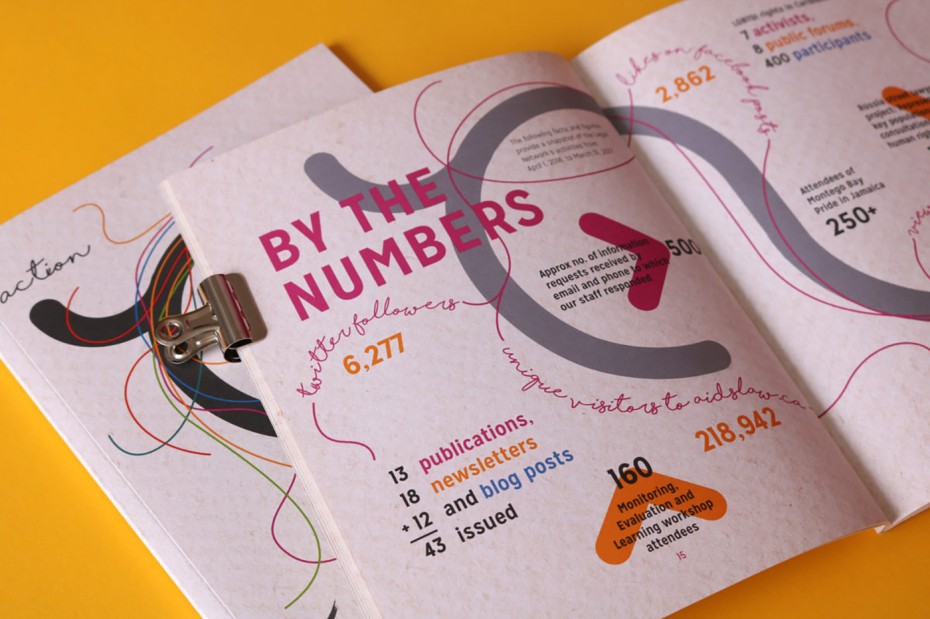

Annual report for the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network

Sampath says that The Public Studio never had a business plan. That's allowed for an expansive practice that includes graphic design but that isn't limited to it. Says Sampath, “It's sometimes hard to even describe what the studio is. We use the term ‘activist’ design studio as shorthand, but if I had to describe what we do, I’d say we run programming. There are so many projects where we haven't actually made a ‘thing’. There's something about how the studio's grown and our understanding of our relationship to the public that's allowed for personal and professional growth in really interesting ways. It has allowed us to remain responsive and know where we can contribute where we shouldn't. We've had experiences where people have asked can you design a poster? And we’ll say no, what you need is a different kind of program. We can help you design a process around that.”

The Public worked with OCAD students over a four-week process that named and unpacked some of the systems that perpetuate violence in the OCAD community. Using art and design, they developed grounding principles to inform models for bystander intervention and the co-creation of safer spaces on campus. Together, they designed and created (Un)Knotted, a participatory installation.

She completely rejects the colonialist, top-down patriarchal model where the designer ‘knows best’. She also rejects the dynamic where the client has all the power because they are paying. Both of those constitute a very capitalist, colonialist and competitive power structure that The Public has no interest in supporting. There’s no competition in community.

Will Novosedlik is a designer, writer, long-time contributor and former editor of Applied Arts Magazine. He is known for a critical perspective on the cultural and socio-economic impact of design, brand, business and innovation.