Will Novosedlik on Building the Biggest Bible since Gutenberg

July 25, 2019

I once had a colleague who joked about how graphic designers were “on a mission from God” to save the world from bad design.

Aside from the Blues Brothers reference, it was a sarcastic reflection on the heroic narrative in which the designer is The Great Problem Solver, and if only ordinary folks would just respect that and let us get on with making their visually impoverished world a better place, we will have fulfilled our mission.

Well, there are missions and then there are missions. What if you really ARE on a mission from God? Imagine you get an RFP to create and produce an illuminated bible. You’re thinking, wow, the last guy to get this gig was Bradbury Thompson for the Washburn College Bible in 1969. But this brief is bigger. Way bigger. Bigger than Gutenberg even.

The brief may not have come from heaven (at least not directly), but in 1998 a bible was commissioned by the Benedictine monks at St. John’s University in Minnesota. It was to be the first handwritten, illuminated Bible commissioned by the Benedictines in 500 years. That’s half a millennium.

Talk about a once in a lifetime opportunity for a hungry scribe.

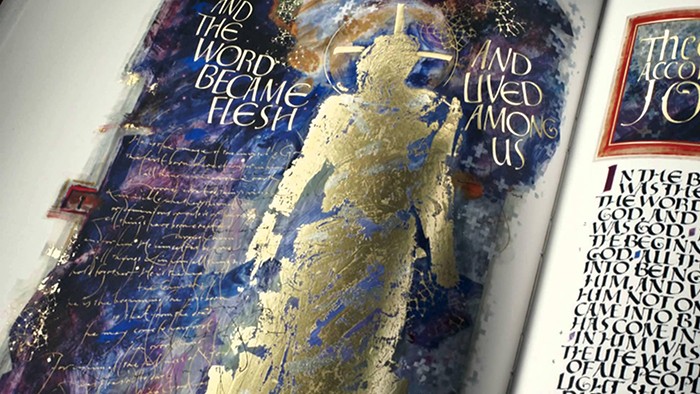

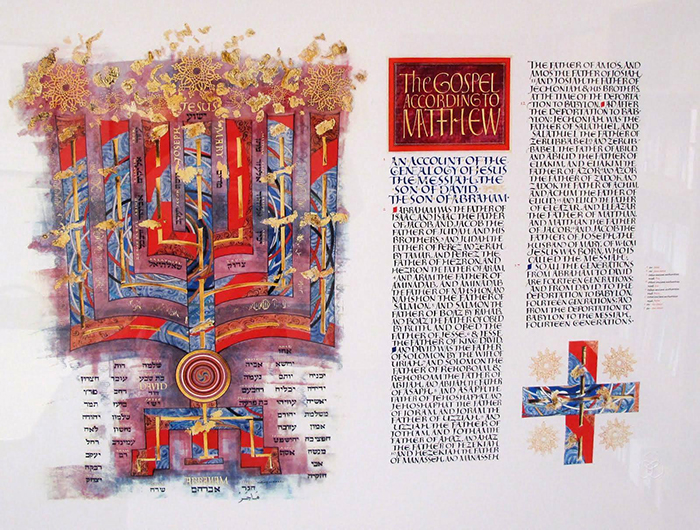

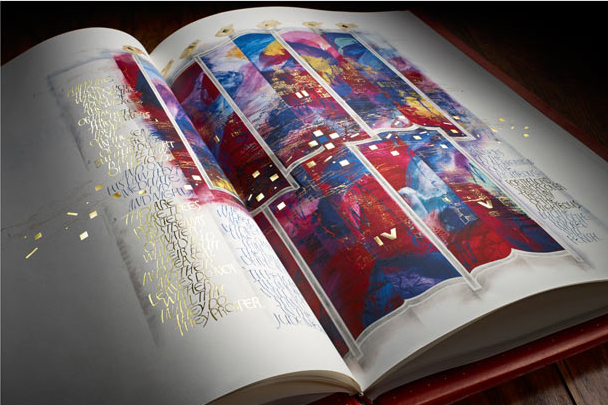

The task went to renowned calligrapher Donald Jackson, senior scribe at Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth’s Crown Office at the House of Lords in London. It took almost 14 years to complete. To read how it was made is a trip through a lost world: “The words are handwritten on vellum (calfskin) using hand-cut quills made of turkey, swan or goose feathers, and ancient inks hand-ground from natural minerals and stones such as lapis lazuli, malachite, and vermillion. The pages are illuminated with the brilliance of 24-karat gold leaf, silver leaf and platinum. The completed work includes 1127 handwritten pages and over 160 major artworks.”

I came across this story by listening to a recent re-broadcast of a 2017 CBC interview with one of the people who produced it. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard of it before. While I am not a religious person, I am respectful of the Bible’s significance as one of Western culture’s founding documents – The Great Code, as Northrop Frye calls it. Not to mention its place in the history of visual communications. So when I heard that the behemoth had been brought back to life through the re-enactment of the 1000+-year-old traditions of calligraphy and illumination, I took note.

Looking at these illuminations, one of their most compelling aspects is the combination of biblical and contemporary references. Thus when you scan the chaotic landscapes of war accompanying the Book of the Apocalypse you find the far-famed horsemen scattered among tanks and oilfields.

This project is not only an unapologetic celebration of the form of the book but also a nod to the realm of the digital. For the Book of Psalms, Jackson’s team recorded sung Gregorian chants, translated the sound prints into visual wave patterns, photographed them and then rendered them by hand as part of the illuminations.

As the page gives over to the screen, the book arts are becoming lost arts. But rather than kill the book, digital technology has allowed the book to be itself so that we can begin to see its true profile and purpose against the backdrop of the screen.

May it live forever.